88. Maud Wagner — Lost Lady of Tattoo Art

Join us as we learn more about the first known female tattoo artist in the United States, Maud Wagner. Born in 1877, Maud grew up to become a circus acrobat and, once most of her body was covered with tattoos, a walking exhibition unto herself.

Discussed in this episode:

Pride & Prejudice Temporary Tattoos by Litographs

Lily Rose at Wayfarer Hotel in Downtown Los Angeles

Tattooed Lady: A History by Amelia K. Osterud

American Jennie: The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill by Anne Sebba

Maud’s Circus by Michelle Rene

88. Maud Wagner — Lost Lady of Tattoo Art

Note: Transcripts are generated, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

KIM: Hi, everyone! Welcome back to another Lost Ladies of Lit mini episode, wherein we dive into another tangential topic that interests us. I’m Kim Askew, here with my friend and writing partner, Amy Helmes.

AMY: Hey, everyone. Kim, I think our regular listeners would be a little shocked to hear that we’re going to be discussing tattoos today. It doesn’t necessarily seem like us. Do you have any tattoos?

KIM: I do.

AMY: You do?!

KIM: You didn’t know that?

AMY: Uh, no! I don’t think I know…

KIM: Yeah, I think you knew. Because I’ve had it the entire time I’ve known you. I have it on my (actually I don’t remember) I think it’s my right hip, the upper buttock area. I have a heart with vines around it.

AMY: Well, I wouldn’t have seen that!

KIM: Well, no, with swimsuits or something. I mean, we don’t wear swimsuits that much. I don’t know why; we live in L.A. but we’re not swimsuit-type people. We’re more like fireside, tea people. So she didn’t know that I had one. I have a heart with vines around it that I got a long time ago. Anyway.

AMY: All right, you learn something new every day.

KIM: That’s hilarious. But Amy, what about you? I know you don’t have one; you don’t even have your ears pierced.

AMY: Yeah, it’s not my aesthetic, but also I think the main reason really is that I would be too paralyzed by indecision to even know what I would want permanently emblazoned on my body. You know, I’ve thought about it. (I’ve never actually really thought about getting a tattoo, but I have, for fun, thought about what I would get if I were going to get one.) It would have to be a word or a quote or something, but how do you even begin to choose? I just don’t know.

KIM: Yeah, that’s the thing. I have a very spontaneous side, as you know. There wasn’t much thinking involved in my tattoo.

AMY: That makes sense.

KIM: But I never regretted it.

AMY: Okay, good, good. Now I will say, and I'm going to hold this up to the screen and show you…. I think, um, Meg who, you know, my old college roommate Meg, she gave me temporary literary tattoos and I have yet to use them, but maybe I will put them on now that this episode is coming up and we can put pictures of my bicep on Instagram with my literary tattoo.

KIM: You should wear them to our next tea.

AMY: Yeah. And they’re all Pride and Prejudice themed. So we have, of course, “Obstinate, headstrong girl.” Uhh.. “Pemberley,” including a silhouette of Pemberley.

KIM: I love that one. Can we fight over them?

AMY: “I am all astonishment.” I like that one. These are made by Litographs, it’s called.

KIM: So Meg, if you’re listening, do you have a tattoo? I don’t think so, but let us know…

AMY: Oh, that’s a good question! Yeah, I don’t know if she has one either.

KIM: Okay, so anyway, listeners, if tattoos are something Amy isn’t passionate about, you might wonder why we’re even discussing them today. It all stems from an outing Amy and I had in January to go have afternoon tea at a venue called Lily Rose in downtown L.A.

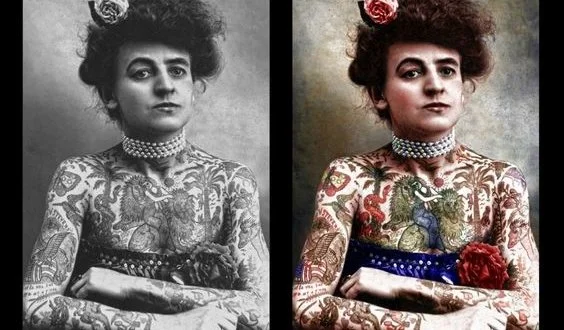

AMY: Yes, so it’s this super cool bar in the Wayfarer hotel… it’s got a funky-bordello vibe with all kinds of cool Victorian art and photos covering the walls. Sort of almost Dark Academia in certain respects. But the centerpiece of the decor is this large, maybe four-foot tall photo of a Victorian woman. She’s got a rose affixed to her poufy, Gibson-girl hair. She’s wearing a four-strand pearl choker. She’s got a truculent expression on her face… AND, she’s wearing a barely there strapless bodice that reveals the fact that her body is covered in tattoos. It’s so surprising.

KIM: Yes, she’s inked with tons of artwork, including two lions across her chest, a hummingbird, butterfly, serpent, palm trees, and an eagle carrying an American flag in its beak.

AMY: So naturally, the portrait caught our attention, and being the curious girls that we are, Kim and I flagged down a waiter to ask him who this was in the picture. You’d think it being the focal point of the bar, he would know. No, he said he wasn’t sure and had to go ask someone.

KIM: Yeah, and he returned a minute later and said, “Oh, that’s Lily Rose,” a.k.a. the bar’s namesake, which made sense.

AMY: Made sense, but god bless him, but he was lying!

KIM: I think he made it up on the spot.

AMY: I think he totally made it up. So I went home and googled Lily Rose trying to find out more about this woman, and I DID find the photo online — it’s everywhere. But the woman’s name was not Lily Rose. It’s Maud Wagner. She happens to be the first known female tattoo artist in the United States. So we’re going to tell you a little about Maud Wagner in today’s episode.

KIM: And of course, we’ll link to some photos of Maud Wagner (and her tattoos) in our show notes. (And, you know, in case any of our listeners want to go get a tattoo after this episode, maybe she’ll inspire you.) So Amy, what do we know about Maud Wagner?

AMY: Well, she was born Maud Stevens in Kansas in 1877, and when she was young, she apparently ran off and joined the circus.

KIM: I love her already.

AMY: Yes. Apparently she worked first as a contortionist, aerialist and acrobat in her early days with the circus. My daughter Julia would love that because she takes aerial lessons. She takes the silks…

KIM: I know, I love that. It’s so beautiful.

AMY: I know, it scares me and Mike half to death to watch her. We’re always joking that she might run off to join the circus someday also. So hopefully she doesn’t pull a “Maud.”

KIM: You know I try everything, right? I did take a lesson in that once and I was horrible. I didn’t have enough upper arm strength to pull myself up.

AMY: Did we do that together because I did that also?

KIM: Did we? Was it with Isobel?

AMY: Was it in Hollywood?

KIM: Yes! It was years ago.

AMY: It was so hard!

KIM: Oh, you have to be so strong to be able to do it. It’s not like you could just unless you’re super strong, you could just walk off the street and do it.

AMY: No, no. It’s like climbing the rope in gym class, but even harder. I was crippled the day after I tried it.

KIM: But it looks so beautiful.

AMY: It does, it does.

KIM: But anyway, we digress. While performing at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 Maud met the man who would become her husband, and he was a tattoo artist. His name was Gus Wagner and he sported 800 tattoos himself.

AMY: Yeah, there’s a book by a woman Margo DeMello called Inked about the history of tattooing and in that book it basically says Wagner gave Maud a tattoo as a way of getting a date with her.

KIM: Yeah, that wouldn’t have worked on me. No.

AMY: No, but apparently a needle and ink is a turn-on for Maud, because she fell for Gus and they ended up getting married and he taught her everything he knew about the art of tattooing. Apparently he did it the old-fashioned way; not with like a gun kind of thing, just a needle and ink. And because she wound up having him decorate most of her body with tattoos, she became an exhibition unto herself. Now instead of being an acrobat, she was a walking work of art.

KIM: Nice pivot… there’s a lot more career stability than as an acrobat, I think.

AMY: Yeah, probably. Safer. Safer to be on the ground. In researching Maud, I came to find out that actually, tattoos in the Victorian era were not as taboo as you might think. Yes, they did kind of start with prisoners and sailors getting them, but some members of elite society actually sported tattoos including Queen Victoria’s eldest son. And there were even some upper class Victorian women sporting ink, too. Apparently (and we’ll get into this in a second, but) Winston Churchill’s own mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, is said to have had a tattoo! Her name was Jennie Jerome, and she was an American heiress (one of the “buccaneers” if you will).

KIM: We love the buccaneers.

AMY: Yes. She reportedly had a tattoo of a snake coiled around her left wrist.

KIM: Oooh!

AMY: Yeah. I say “reportedly,” because it was written about in a newspaper article in 1894 and I’ll just read from that:

“There are certain women of the world who capture public attention to that degree that everything they do is promptly chronicled. Lady Randolph Churchill is one of them. When returning home from India with Lord Randolph she noticed a British soldier tattooing a deckhand… She had the artist brought before her and asked him for some designs. He suggested the Talmudic symbol of eternity- a snake holding its tail in its mouth. Lady Randolph was charmed and bared her arm for the operation. Lord Randolph swore and protested. But the tattooing was done- so it is said, at least- and it is described as a beautifully executed snake, dark blue in color, with green eyes and red jaws. As a general thing it is hidden from the vulgar gaze by a broad gold bracelet, but her personal friends are privileged to see it and hear the story of the tattooing.”

KIM: Oooh, I love that. I’m not going to get another tattoo, probably ever, but that sounds really cool. Good for her!

AMY: Yeah, if it looks like a bracelet or whatever. But here’s the problem. When you look up photos of Jennie (and there are many) there is no snake tattoo to be found on any, even potentially hidden under a bracelet. You just can’t find them. She would have gotten the tattoo when she was around 40, supposedly, but no one’s been able to find any photographic evidence she was sporting ink.

KIM: That would be hard to hide.

AMY: It would be. And I’d love for that story to be true, but it could be fake news. They even kind of said in the article, it’s almost written as if they didn’t have an eyewitness account. Like, “So it is said,” you know? But I want to credit a web article by Amelia K. Osterud, a historian and author of the book Tattooed Lady: A History. She provided the intel on all this about this mystery of Jennie Churchill’s tattoo. Anyway, it’s really making me want to go read Anne Sebba’s 2007 biography of Jennie Churchill. Even if she didn’t get a tattoo, she sounds like she was quite the spitfire in many other ways, and if you’re into the Gilded Age like we are, she’s a lady you ought to know better.

KIM: I’m super into that idea. Anyway, getting back to Maud Wagner, she died in 1961. Because she and her husband spent so much time on the road in traveling vaudeville shows, county fairs and amusement arcades, the couple is credited with helping spread the tradition of tattooing across the United States.

AMY: There’s also a historical novel based on her life called Maud’s Circus by an author named Michelle Rene (I’m not sure how that’s pronounced) But If you liked Sara Gruen’s 2006 novel Water for Elephants, this one sounds like it would kind of be in that same sort of world, which would be fun.

KIM: Oh, yeah, and that’s making me think of one of my favorite books ever, but the name is not coming to me. The wonderful book… it’s like a cult favorite.

AMY: It’s not the lobster boy?

KIM: No, no, it’s not called The Lobster Boy, but yeah it’s set in the circus. Geek Love!

AMY: Yeah, that’s what I’m thinking of! Geek Love.

KIM: I didn’t hear you say that.

AMY: I didn’t say it, but I feel like there was a Lobster Boy in Geek Love.

KIM: Oh yeah, there is. Yeah, Geek Love, which I read a few years ago again because Eric had never read it and I had him read it and he loved it. Such a great book.

AMY: Yeah.

KIM: We would never have known about Maud if we hadn’t gone to tea together and seen her photo so once again once of our field trips turned into inspiration. It always does.

AMY: Yeah, although still not as great as our Cate Blanchett sighting during our afternoon tea we had at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills. Remember that?

KIM: Oh, I won’t ever forget it. We were having a brainstorm for one of our projects that I think maybe our first book or something.

AMY: Yeah, and we thought, “This is all meant to be, the fact that we’re seeing Cate Blanchett here!!!”

KIM: And it was!!

AMY: Anyway, it’s making me think we need to schedule another of our fancy teas. Let’s get it on the books.

KIM: Yes, let’s, because who knows what adventure might await. So that’s all for today’s episode! Be sure to join us again next week when we’ll be discussing the author Tess Slesinger and her unforgettable Modernist novel, The Unpossessed.

AMY: We’ve got Dr. Paula Rabinowitz joining us next week, and get this: Tess Slesinger’s son, Peter Davis, will be with us, too! How cool is that?

KIM: I cannot wait! Bye, everyone!

AMY: Our theme song was written and performed by Jennie Malone and our logo was designed by Harriet Grant. Lost Ladies of Lit is produced by Amy Helmes and Kim Askew.

87. Kay Dick — They with Lucy Scholes

Note: Transcripts are generated, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Episode 87: Kay Dick — They with Lucy Scholes

AMY: Hey, everybody, welcome to Lost Ladies of Lit, the podcast dedicated to dusting off great books by forgotten women writers. I’m Amy Helmes, here with my writing partner Kim Askew.

KIM: Hi, everyone! Our guest today wrote of the lost dystopian masterpiece we’re going to be discussing: it’s “a surreptitious, later-career aberration…whose strangeness never seeped into what she wrote after.” So intriguing, right?

AMY: A weird one-off! Yeah, that is interesting. And Kim, as you said, this novella, They by Kay Dick, is dystopian, which is usually more your speed, but I actually loved it, too, I’ll confess.

KIM: I know, and I think, Amy, that this podcast is changing you, because you thought you didn’t like dystopian or sci-fi or noir, but I kind of feel like maybe you just thought you didn’t like them?

AMY: Could be. I’m not sure I’m going to agree 100% yet, but I’m definitely a fan of this book, and I’m of course a fan of our returning guest, the wonderful Lucy Scholes.

KIM: Yes, we are so glad to have her back on the show! So let’s raid the stack and get started!

[introductory music]

AMY: Our guest today is Lucy Scholes, and after you listen to this episode, you may want to go back and listen to the episode we did with her last September on Rosamond Lehmann’s Dusty Answer. Lucy is a London-based critic who writes for The Times Literary Supplement, The Observer, The Financial Times, The New York Review of Books and Literary Hub, among others. In addition to all that, she hosts “Ourshelves,” the official podcast of Virago Books. Every two weeks you can find Lucy interviewing big names in the literary world, talking to them about their own favorite books, music, TV shows and more. We highly recommend you go check out that podcast.

KIM: Yes, it’s one of our favorites. And in Lucy’s must-read column for The Paris Review, “Re-Covered,” she writes about out-of-print and forgotten books, which as you can imagine is a treasure trove of lost ladies of lit. In her August, 2020 column, she wrote about Kay Dick and They; we’ll link to the column in our show notes. Now, Lucy is also the Senior Editor of McNally Editions, and McNally has recently issued a new edition of They with an afterword by Lucy. Welcome, Lucy! We’re honored to have you back!

LUCY: Well, thank you both so much for having me back; I’m really grateful that you invited me on the show again! It was such fun last time.

AMY: Yeah, absolutely. In your Re-covered column on Dick, you write “Kay Dick is a name all but forgotten today, but in the mid-twentieth century she was at the heart of the London literary scene.” I love the story of how you discovered her! Do you want to share it with our listeners?

LUCY: Yes, so it was about two and a half years ago now, I guess not long before the pandemic hit, I stumbled across an obituary that the British newspaper the Guardian had run for Kay Dick when she died in 2001. But what was so fascinating about this particular piece was how spiteful and nasty it was. It was written by a writer named Michael de-la-Noy, and he accused Dick of having —and I’m quoting him directly here: “expended far more energy in pursuing personal vendettas and romantic lesbian friendships than in writing books.” The thing was, though, the description of her life that then followed sounded so intriguing, and so full of achievement! So, I mean, she published ten books of her own, and edited various anthologies and magazines—which all seems pretty productive to me, or by my standards, at least it is! But anyway, the very worst thing that de-la-Noy had to say about her— and he draws the obit to a close by describing her as “a talented woman bedeviled by ingratitude and a kind of manic desire to avenge totally imaginary wrongs”— so this only made me more fascinated to find out a little bit more about her. So I immediately tracked down copies of her books.

KIM: When you actually started reading her, though, you were a little bit disappointed. Do you want to talk about that?

LUCY: Yeah, I was a little bit. Her first five novels—which were published between 1949 and 1962—weren't terribly exciting. They’re written very well, but they’re just not especially noteworthy; I guess I’d describe them as elegant novels of manners. They’re set in polite society and they now feel a bit dated. But then I kind of persevere. I kept going because I thought there would be something maybe there eventually, and I picked up THEY: A SEQUENCE OF UNEASE, which was first published in 1977, and from the very first page—I mean, I guess really from the title. I mean who titles a book with the subtitle “a sequence of unease”?—I knew I was reading something very special. And I think this was partly because the voice was so utterly different to that I’d encountered in her earlier work, as was the style—it was very pared down, stripped back, quite raw and visceral—and then there was the fact that it was this kind of strange and uneasy dystopian tale, set in an England that’s both instantly recognizable, and also utterly alien.

AMY: And you mention that subtitle, and I feel like that’s the first I’m kind of hearing of that subtitle. Does the McNally edition use that?

LUCY: Yeah, I think we use it on the sort of inside page.

AMY: Okay, it’s not on the cover.

LUCY: No, and I think even when it was first published, They was very on the front page, but then it has got this subtitle, this kind of strange one.

KIM: Yeah, I love the beautiful spare cover with the striking image and then the word They. It’s very nice.

AMY: But yes, “A Sequence of Unease,” though, as you said, tell me more! But let’s just back up some and find out more about Dick’s life. She was born in 1915 to a single mother who had left her somewhat privileged life to go be part of the bohemian cafe society. So, Lucy, can you tell us a little more about Dick’s childhood?

LUCY: Yeah, it was fairly unorthodox, I think, to say the least! Her mother had her illegitimately, and in those days that can’t have been particularly easy. I’m sure it meant that she was ostracized from her own parents if she hadn’t already made the break herself. And Dick told the wonderful story that the day after her mother gave birth to her, rather than heading home from the hospital, the new mother, with her baby in her arms, headed straight for the Café Royal, which was one of the most famous night spots in London, popular with this bohemian, fast-living crowd—and everyone there toasted the new baby with champagne! And Dick called this her “baptism” later, because she hadn’t had a church baptism. This had been her entry into the world.

KIM: I love that story; what a start in life!

AMY: I know, Kim, why weren’t we going straight to the nightclubs from the hospital?

KIM: Yeah. It sounds so glamorous. But then, I guess when she was around seven, her life changed a bit. Do you want to talk about that?

LUCY: Yeah, this was when Dick’s mother married the Swiss man who she’s been previously having an affair with, I guess you would put it. Mother and daughter had always lived quite a sort of cosmopolitan, privileged life— and this was paid for by Dick’s mother’s lover. But the marriage gave them access to a very different world, something slightly different to the more haphazard, bohemian existence they’d lived up until this point. Dick was sent to boarding school out of London for a while, but I don’t think she got on particularly well there, so she was taken out of that school and then sent to school in Geneva in Switzerland, where she apparently lived with a host family, and this was much more to her liking.

AMY: So did she have ambitions to write from a very young age? How did she get her start?

LUCY: Well, I think her stepfather had been quite wealthy at one point, and by the time Dick came of age, he’d lost quite a lot of his money, which meant she had to go out and earn her own living. But I don’t think she minded doing this; if anything, she had quite a great time! She worked as a bookseller, and as an assistant editor on various magazines, before being quickly promoted, and then she eventually started writing novels of her own.

KIM: So then it sounds like she basically reconnected with this bohemian community she’d been welcomed into as a child, right?

LUCY: Yes, absolutely! I found a wonderful interview that she gave a newspaper in the 1980s in which she recalled leaving home at the age of 20 to gad about London with what she describes as “a louche set”—and she talks about wandering Soho with her bisexual friend Tony, both of them wearing capes and sporting canes! Looking a bit like Oscar Wilde I’d imagine!

KIM: I love that image!

AMY: Totally. So then we know that she worked at Foyles bookshop in London's Charing Cross Road and then when she was only 26, she became the first woman director in English publishing at P.S. King & Son. She later became a journalist at the New Statesman. While she was a journalist she wrote under the nom de plume Edward Lane. And she also edited the literary magazine The Windmill. Do we have any idea why she used a male pen name ?

LUCY: To be honest, I’m not sure. She used a couple of different male pen names for various projects, and “Edward Lane” was the most famous of the two. I doubt she was the only woman writer doing this at the time, but I’m also inclined to say it might not necessarily have been for the reasons that we might assume. In that interview that I just mentioned, she says at one point that she “cannot bear apartheid of any kind—class, colour or sex,” and then adds that “gender is of no bloody account.” So I think she was clearly quite a character, very dramatic, and, I suspect, liked to play with and tease people, so I would imagine she would take a certain amount of delight in pretending to be someone else, you know, male or female.

KIM: And given all that and what you told us, it’s actually unsurprising that she and her partner of many years, Kathleen Farrell, actually entertained some of the most successful and popular writers of the era in their home. But how were Kay’s own books received by the public and the critics?

LUCY: She got very decent reviews. None were bestsellers, or huge hits, but the writing was generally well respected. The novels were often described as “Proustian,” these early novels, which I think is pretty complimentary to be honest. And then in the early 1970s she went on to publish two volumes of interviews with her writer friends—Ivy and Stevie, as in Ivy Compton Burnett and Stevie Smith, and then a second volume called Friends and Friendship, which included interviews with people like Brigid Brophy, Olivia Manning and Francis King. And these were also well received. They’re not in print today, but amongst certain people today who are interested in these writers, they’re considered important artifacts.

AMY: I’m hearing some potential subjects for Lost Ladies of Lit in that list.

LUCY: Yeah.

AMY: And I love the fact that we can potentially mine some info about them from Kay Dick if we were able to get our hands on a copy of either of those books that you just mentioned.

KIM: I love that idea.

LUCY: Yeah, no I definitely recommend it. They’re out of print, but you can get second-hand copies, and they are a sort of wealth of information because she was very good friends with these writers so they have a very personal tone to the interviews, not the kind of classic interviewer-and-subject who don’t know each other. There’s a really kind of intimate element.

KIM: Oh, that sounds so good. So, let’s go back to that not entirely complimentary obituary you mentioned earlier. That was pretty harsh.… Do you want to talk about the dichotomy between what was written in that obit versus what you found out about her doing your research?

LUCY: Well, she was obviously not someone who suffered fools gladly, and she could certainly be prickly, and she did sometimes hold grudges, but she was also a woman whose friends meant everything to her. I guess because her own family life had been rather unconventional, as we’ve discussed, she had no children, and no life-partner—though she and Farrell did remain close, and an integral part of each other’s lives, long after they broke up. But this meant that Dick’s friends were everything to her. And to many of these friends she was deeply loyal and supportive. I’ve had the great luck of getting to know the wonderful executors of her Estate, as well of some of her other friends and neighbors from her later life, and all of them have spoken with such fondness of how much fun she was, and how much she loved spending time with people, and introducing the people she loved to one another, which I think is such a rare kind of talent and a gift to have, wanting to share your friends around with other people. And also they’ve all mentioned about how much she loved young people. She hosted these soirees in her flat in Brighton—which was where she lived after she left London in the 1960s onward after her relationship with Farrell ended. And apparently she served cucumber sandwiches and glasses at these and everyone drank Campari and orange or glasses of champagne. I mean, it really sounds rather wonderful. And she devoted a lot of time, I think, to encouraging young, up and coming writers too apparently. In fact, the minute that awful obit was published in the Guardian, the paper received quite a lot of complaint letters from her friends who were outraged that she’d been depicted so shoddily in it. If I may read an extract from the letter her friend and neighbor the writer Roy Greenslade wrote. He writes:

She was, in fact, a most perceptive critic, preferring too often to spend her time reading the works of others rather than writing herself. Few people read as much as Kay. “Darling, I’ve just been rereading Scott,” she once said. “He was brilliant.” I asked: “Which novel?” “All of them,” she replied, without the least sign of boasting. Her other great talent lay in introducing people she met to her wide network of friends and contacts. She loved our children, helped them, made them laugh, made them think. Both of them, like my wife and I, benefited from knowing the lady with the cigarette holder and the succession of dogs along the terrace.

KIM: That is so beautiful. I mean I love that her friends rallied…

AMY: Coming to her defense.

KIM: I know. Good for them, too.

AMY: And also, that description that he just painted, if you Google images of her, that’s sort of what comes up. She looks like she could be a little intimidating in the photos, but then she also looks extremely interesting. Like somebody you want to know.

LUCY: Yep, yep.

AMY: So let’s get back to her novel They. When you read it, was it a surprise given that you started with these novels of manners? How shocking was it for you to then stumble upon They in the list, and like, “What?!!”

LUCY: Yeah, it was completely shocking. Like I said, I enjoyed the first novels, but I wasn’t particularly excited by them. And I guess I’d been lulled into a false sense of security after reading a few of them. And then I picked up They, opened it up, and it was a complete surprise.

KIM: I love that you kept going and didn’t stop too soon. That would have been really sad for all of us. It’s a good lesson to keep reading!

LUCY: Perseverance! It’s important!

KIM: Yeah.

AMY: I purposefully didn’t look up anything about the book before I read it, either and yeah, I was like, “Whoa!” I don’t think we’re going to give away too many spoilers, but we will set the premise of sort of what the book’s about. So Lucy, do you want to go ahead and do that?

LUCY: Yeah, it’s not a hugely plot-heavy book, which isn’t to say nothing happens in it—far from it, in fact—but the way it’s written, the chapters can almost be read as stand-alone vignettes. They seem to be linked by the presence of the same main character, but there’s no obvious chronology between them. In essence though, the novel is set amongst the countryside and the beaches of coastal Sussex, in England, which is home to the narrator—a writer—and her—or his—their gender is never revealed—various friends, all of these people are artists or craftspeople of some kind or other. It starts off all very beautiful and bucolic, but pretty soon, you realize that something is amiss. Plundering bands of philistines are actually prowling the country destroying art, books, sculpture, musical instruments and scores, punishing those artistically and intellectually- inclined outliers who refuse to abide by this new mob rule.

AMY: Is there any favorite passage of yours from They that you’d like to read to kind of give listeners a little bit of a feel for the prose?

LUCY: Yeah, this was kind of a tricky ask, because I think each chapter brings a bit of a different dimension to the fear. And so I wanted to give you a bit of a taste of it. But I’ve chosen one from the chapter called Pebble of Unease. So we’ve got the narrator and a friend of hers are walking on the downs, which are the hills around Sussex, and although we’ve seen smaller bands of these “They,” these mysterious “They,” this is the first time we’re seeing them en masse as it were. Okay.

We turned round. There they were on the ridge. We looked behind us. A similar column in line, each one holding a pole to match his height. They began to move downward with deliberate precision. ‘Hold my hand,’ Julian said. ‘We must go on, as we intended, homewards.’

They broke formation, in slow motion, gyrated towards us, executing a pattern of zigzagging movements, crossing and recrossing one another’s steps.

‘If we’re lucky, we’ll miss the symmetry of their course,’ Julian said.

We felt them as rank after rank of them moved past us. Pockets of air hit us as their intricate patterns of movement slid past us. I stumbled. Julian pulled me up fiercely. ‘We mustn’t alter our pace or sway in the slightest,’ he said.

As we moved up the track they surrounded us on all sides, never deviating an inch from their rigid exercise. Others followed in their tracks. The crossings and recrossings of their lines went on, relentlessly slow, totally in unison. I was sweating. I was tired. I wanted to pause. Julian urged me upwards. I could see the kissing-gate in the distance. Another relay began their descent. ‘Don’t look back,’ Julian said. ‘Keep with the stream of our natural route.’ I saw one of the poles as one of the men moved a fraction past my body: it shone like steel. To the left and the right of my vision they swirled. I pressed my arms closer to my body, fearing I might knock against one of the poles. Their precision was monstrously accurate as they repeated the movements of those who had descended before them. I caught glimpses of eyes, heads, chests, arms, legs, and, ever, the shining steel poles. I saw the last three of them as they veered toward us. One went to the right of us, the other to the left. Quickly Julian pushed me away from him as the third one crashed into the space between our two bodies and went on.

We reached the kissing-gate. ‘Don’t look back,’ Julian said. ‘We must not appear inquisitive.’ He sounded frivolous.

AMY: It reminds me kind of of the Death Eaters from Harry Potter. Like, “Oh my god, they’re coming” This terrifying mass inching towards you; how frightening that is.

KIM: And that unease is so perfectly illustrated in that passage. Each of these chapters is its own story that could be in The New Yorker on its own without even reading the rest of them, although as a complete piece it’s beautifully woven together, but they are definitely stand alone and they all have that sense of unease. It also reminded me a bit of this book called Wittgenstein’s Mistress. It’s by David Markham. David Foster Wallace called that book "pretty much the high point of experimental fiction in this country." (Meaning the U.S.) Have either of you read that one?

LUCY: No, I haven’t. I think you’ve mentioned to me a couple of weeks ago that it was similar so I’ve been wanting to get hold of a copy ever since. I’m fascinated by it.

KIM: Yeah, it came out about a decade after They, but it has some interesting parallels, which is what made me think of it. It’s one of my husband’s favorite books, so I read about it because of him and I really loved it. The woman named Kate is the narrator. She believes she is the last human on earth (and she’s likely mad), but she’s remembering all the art and literature that have shaped her, from Brahms to Shakespeare. As you said, in They, the narrator is trying to retain the ability to write and, along with the other artists in the book, is trying to remember the works that have shaped them. And it really feels like the world is dying around them — for sure art is dying and maybe individuality even — and these are the last few vestiges of what humanity once was.

AMY: Yeah, it’s like literally the narrator will return to their cottage and notice that books are missing from the bookshelf or pages are missing from the bindings.

KIM: Yeah, on a certain level that could be innocuous, but within the idea of all of the books being slowly taken away, I think to people who love art and books and music, there’s nothing more chilling than the idea that these things are being taken away.

AMY: Lucy, I had finished the novel, started reading your afterword, and you mention that the narrator could have been a man or a woman, and I was like, “Wait, what?” I was just automatically reading it as if the narrator was a woman. It made me kind of want to go back and reread it thinking of it being possibly a man as well and seeing if it would give me any different understanding of it. But why do you think she kept the storyteller’s gender unknown?

LUCY: Yeah, it’s a tricky one, isn’t it? I would imagine that if it’s got to do with anything, it’s more her thoughts about gender being of little interest. I have to confess, I agree with you. I automatically think of the narrator as a woman, but I think that’s because I came to They after reading five of her earlier novels. I think I was already conditioned to think of the narrator in a certain way. So Sunday, the novel that she wrote before They is highly autobiographical, as is The Shelf, the novel she wrote after They, and even though They is set in this kind of strange, parallel version of England, I think it’s a book about friendship and love and art, all the things that Dick held dearest. So to me, it still feels like it’s actually a deeply personal book to Dick.

KIM: It definitely feels that way when you’re reading it. It almost feels like a diary or a memoir or something. And as we said, people and books are literally disappearing from the narrator’s life on a daily basis. Yet, the narrator makes this choice over and over in each of the stories to continue living alone. It’s an explicit choice to be a target, given the nature of these mobs, which targets single people. In doing so, he or she is taking a stand to continue to be a writer and also maintain that artistic part of their personality in spite of everything they are up against. Dick definitely seemed to live by her own rules. What do you think she’s trying to say about non-conformity and artistic integrity in They?

LUCY: She’s upped the stakes in They, of course, in that those who refuse to conform are risking actual bodily harm and violence , and being killed. But even without such terrible threats hanging over one’s head, I think she’s explaining that being an artist involves a certain degree of bravery, right? It’s a risky business. In Friends and Friendship (the second books of interviews that she published) she writes, “it is an extremely courageous act to be a writer, painter, composer, because you are out on your own, in limbo, totally unprotected, not much encouraged, driven only by some inner conviction and strength, and the discipline is yours alone.” So this is clearly what she believes, and this—I think—is what lies at the heart of They.

KIM: That’s a perfect quote to give context to the book. Wow. That completely makes sense with the narrator.

AMY: In your afterword, you talk about grief being an important theme in this novel. And it’s also key in the genesis of how the book came to be. Can you talk about what you think she might have been trying to convey about grief in the book?

LUCY: I find it so fascinating that she takes the time to note how influenced she was by this particular newspaper article—it was called ‘Coping with Grief’ that apparently described this new kind of psychiatric treatment in which one’s emotions are “burnt out” and the grief is expelled—she mentions it on the imprint page of the book, so it’s clearly super significant; and the “They” of the book’s title have a hatred of people showing their feelings; everyone has to be numb and calm, drama in any shape or form has been completely outlawed. It sort of suggests to me that Dick might have felt sort of stymied by something—whether it was polite society, convention, that idea of the English stiff upper lip, maybe the struggle of living in a world that didn’t afford her romantic relationships with other women the same degree of respect that heterosexual couples around her got. What we do know for sure, though, is that she went through a period of intense and prolonged loss and grief in the run-up to writing They, and I would suggest that she was still trying to kind of process all her emotions—she was still grieving when she wrote this book.

KIM: Yeah, so, as we mentioned in the intro, They came out later in Dick’s career — I think you said about a fifteen-year gap. Can you tell us a little bit more about what was going on during that gap and more about what might have driven her to write such a divergent work?

LUCY: Yeah, so those fifteen years were really quite traumatic for her, I think. A few major things happened in quite quick succession: so her twenty-odd-year relationship with Kathleen Farrell broke down and the two women parted ways, though as I said, they did stay in touch but they weren’t together after that; Dick tried to kill herself, which she writes about in Friends and Friendship; and a woman that she had a brief affair with in the aftermath of her relationship with Kathleen, this woman went on to commit suicide (and this is talked about in much more detail in the novel that that follows They, a novel called The Shelf). And during this time Dick also moved from London to Brighton, she was getting older, she was no longer I guess at the heart of the literary scene that she had been for many years, and I think she was struggling to finish various writing projects that she’d begun work on, a couple of big biographies that she started and they never got started. And you know if you look at her archive there’s a lot of kind of unfinished projects there. I think all this loss seems to have taken quite a toll on her, and it seems to have drastically changed her writing as well. You know, I wrote in the afterword that in many ways, They reminds me a lot of works like Anna Kavan’s novel Ice, which was published in 1967, and this is this kind of strange, enigmatic, almost psychedelic novel in which this man is pursuing a woman across a snowy, post-apocalyptic wasteland. Kavan famously switched the register of her prose after a huge kind of mental breakdown—she started out by writing relatively conventional, what you might describe as women’s fiction, and then she ended up in an insane asylum for a while, and she emerged out of this with bleached blonde hair and this kind of crazy heroin addiction, and a whole new way of writing. And I think something similar also happened to Dick’s friend Christine Brooke-Rose, another writer from this period. She survived a near fatal kidney operation in the early 60s, and then started writing much more avant-garde after that. Works that Dick, herself, described as quite Orwellian. And I think something similar must have happened to Dick; I mean her life was upended. Maybe not quite so dramatically; maybe through a series of events. But I think she became a different writer as a consequence of this huge upheaval. They is completely different to the novel that precedes it, Sunday, and there is that large gap in which something is obviously happening during that time.

KIM: In his February New Yorker article, that you have a cameo in, Lucy, Sam Knight called They a collection of “quietly horrifying stories,” and I love that description. They is quiet in almost this sort of cozy English way. The characters interact with each other and the normal sort of things they say and do like trimming rose bushes, having tea together, having parties. They’re staying calm together and mostly stoic, while at the same time all this horrible stuff is happening around them and to them.

AMY: You’re right, Kim. There’s something very calm and almost pretty to me (I don’t know if that’s the right word) but that’s kind of how I felt in reading it. So much attention is paid to color in the stories, so I’m just going to read a little excerpt that shows that.

[reads excerpt]

To me, that reads like a painting, which is appropriate because the book is so much about art and tangled up in that.

KIM: Yeah, it almost seems like everything could be more vivid to the narrator because these other things are being taken away. I don’t know. Anyway. The book came out in 1977. Do you want to maybe talk about maybe how it fits in, or doesn’t, I guess, with other dystopian books from this time and maybe hone in some more on what political statement Dick may have been making with They?

LUCY: Well, I think as I just said, it sort of sits alongside other “experimental” novels from the period—like Christine Brooke-Rose’s Out (1964), which is a post-apocalyptic race reversal story, Anna Kavan’s work, and also Ann Quin’s novels too, if anyone’s familiar with her writing.. But then, too, there are also similarities with earlier works, like Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 with the book-burning firemen. I think it takes something from that. I think more generally though, the 70s was quite a time of great unrest, especially here in England, where we were dealing with things like the miners’ strikes, electricity blackouts, IRA bombings, and a lot of racial prejudice and hatred. They doesn’t reference or engage with any of these things specifically, but I think the miasma of fear and violence that hangs over the book surely draws on things that were going on in the real world at the time. I would imagine that in a sense, Dick was responding to the real world in her fictional version.

KIM: Yeah, and it also feels very timeless, too. I think we’ve been going through similar upheaval, so I think reading it, you wouldn’t necessarily know that it was written in the 70s.

AMY: No. And in fact, I was thinking it was set in the 1930s until I saw the word television set. But yeah, it’s very nonspecific, as you say.

LUCY: Well, I think, also, you have to remember that she was not young when she wrote this, right? She’s not like a young writer starting out in the 70s. She’s already in her sixties. So i think some of the more traditional elements about it, whether it’s the more pastoral scenes or some of the more dystopian elements are definitely harkening back to that sort of 30s and 40s version of dystopia and I think that makes sense because if you think about the time when she was young and when she was being formed as a writer, let’s put it that way.

AMY: Right, I’m thinking of fascism and all the things that the world was facing. That’s where I was approaching it.

LUCY: Yeah, and I think that bit I read earlier with the hordes of men coming down the hill, they almost seem like a fascist rally, right? That’s what it makes me think of.

KIM: Absolutely. So it is a very dark book. (And it actually made me think of the 2015 film The Lobster--I don’t know if I saw that with you, Amy.)

AMY: No, I’ve never seen that.

KIM: Okay. Singledom is also deemed unacceptable in that film: single people are given 45 days to find romantic partners or otherwise they’re turned into animals). It’s very surreal, but also very chilling.

AMY: As if single people don’t have enough pressure on them.

KIM: I know, seriously. Yeah. They is cataclysmic, basically. But do you feel that there’s hope to be found in it Lucy?

LUCY: I think I do, though perhaps only a fleeting sense. But then I do think there are moments of serenity and beauty in this book, friendship and love. And I also think there’s a strange sort of hope to be found in its style even—because it’s written in these vignettes, so even if one chapter ends in utter darkness—and some of them really do! They’re kind of horrific—you then turn the page and you start a sort of new story in this world. And I guess, I don’t know, it seems to be saying that as long as there are people willing to resist, there’s hope, and that even the tiniest action can be an act of resistance. And I also think it’s probably important to think about how that final story in the book ends, you know: “Hallo Love.” The last lines of which are: “My tension relaxed. There were possibilities. ‘Hallo love,’ I said, greeting another day.” And I feel that if you’ve got these vignettes that you can technically move around, there must be something about ending on that hopeful note.

KIM: Oh, yeah, and actually, you need that I think.

LUCY: Yeah. That’s true

KIM: You want to believe there’s something that you can do and that the characters can do to retrieve what was lost.

AMY: Yeah, and you get a sense throughout that the narrator just approaches everything like “just keep going. Just keep going.” In that New Yorker article we mentioned earlier, Knight quotes literary editor Becky Brown as saying, “It’s incredibly unusual to find a book this good that has been this profoundly forgotten. That almost never happens.” And Dick herself really loved this book too. So why do you think it did kind of fall off the face of the earth (well, until recently, thank goodness). Would you agree that this novel seems kind of appropriate for today? (I hesitate to use the word “relevant” because I remember from the last episode you don’t necessarily think a book needs to be relevant to be enjoyed…

LUCY: [laughing] Well done.

AMY: But I think this one in particular does seem like it really is relevant.

LUCY: Well, firstly I completely agree with Becky. I think this particular cocktail rarely happens when you find such a wonderful book so forgotten, so relevant for the day it comes out in again. So all of us involved with the various re-prints have been incredibly lucky, and we kind of know this. And I guess every time I listen to any episode of this show and it’s an author I’ve never heard of, I end up asking myself the same question: Why has this person been forgotten? Why do I not know about them? And of course, the sad thing is that it’s often quite arbitrary, right? There are so many reasons why a book falls out of print. I guess in the case of They, the reviews weren’t amazing—a few critics did get it, others hated it, and some were just rather bemused by it. The Sunday Times called it “a fantasy sprouting from some collective menopausal spasm in the national unconscious.”

AMY: Oh, stop.

KIM: Yeah. Harsh.

AMY: Blame the uterus.

LUCY: Right. I mean, I also don’t really know what that means, but it doesn’t sound particularly great, let’s put it that way. I mean, the book did win the now defunct prize called the South East Arts Literature Prize, but it didn’t sell especially well, so it quickly fell out of print and thus was forgotten. Obviously there were people who recognized it throughout the years, but by and large it’s been off the radar. I think maybe the world wasn’t quite ready for it. Certainly didn’t quite know what to make of it—and although I’ve just listed all those other novels from the 60s and 70s that it shares similarities with, it is a little bit dated in other ways, a little bit old-fashioned, perhaps even quaint, we might describe it as. It does hark back to a sort of earlier era of English fiction. All the cream teas, and seed cakes, the pruning of the roses that you’ve mentioned, the beautiful countryside. And I think in terms of striking a chord today, sadly I guess it’s because the vision presented in the book feels closer to home than ever before right? We’re all quite conscious of certain freedoms being eroded. Mob rule has taken on this kind of horrifying new relevance, whether it’s actually out on the streets or online. And we’re on the brink of a climate catastrophe yet people are looking away and not kind of engaging with it. So I think it feels quite often that “They”—whoever “they” are—are already amongst us.

AMY: I just want to go back for a second to the menopausal spasm because I feel like if there were an entire genre, I would read it.

LUCY: Yep.

AMY: The “menopausal spasm” section of the book store. I’d probably head over there.

KIM: I think that’s a great podcast name: Menopausal Spasm. Sign me up! I’m going to download that one!

AMY: But you’re right, when you talk about the quaintness of the book, that’s what appealed to me in terms of somebody that doesn’t typically like dystopian, this book does not have that “Bladerunner” feel, which I don’t get into, so I think that’s maybe why I liked the book.

KIM: Yeah. That makes sense. Lucy, as we said, you are senior editor of McNally Editions, which is so cool, and we’re so excited to read some of the other books in the series. You must love all of them, of course, but are there one or two you’d like to particularly share?

LUCY: Thank you very much for this! Yeah, I would obviously recommend them all, as you said, but there are a couple already that are out alongside with They that I think your listeners would be particularly interested in. The first is Winter Love by Han Suyin, which is a beautifully kind of brittle story about a doomed love affair between two women in London during the Second World War, and then there’s Margaret Kennedy’s Troy Chimneys, which is a Regency-set tale about a man torn between two different sides to his personality, and this reads like a lost Jane Austen novel; so it’s completely delicious. And last up, if I may, there’s soon to be published is Penelope Mortimer’s utterly brilliant Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting, which is the most incredible story of a housewife’s breakdown in late 1950s England, and her desperate bid to arrange an abortion for her student daughter, so as to prevent history repeating itself. I’ve been a huge fan of Mortimer’s writing for a long time now —I think she’s a genius—and it’s a real thrill in particular to be re-issuing this one in the States.

KIM: I feel like I’m being pulled in three different directions here. Like I can’t even decide which one to read first!

AMY: I know! I’m salivating!

KIM: Yeah, totally. All of them, but then the Jane Austen and then the Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting… you actually sent us Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting, so we can read that.

LUCY: Please read it! I mean, I’m sure everyone on this show says this, but like I say, Mortimer is such a favorite of mine and she’s sort of under-recognized, let’s say. It is of its era, absolutely, but it just feels so relevant as well, particularly with issues of aborition going on in the States right now and stuff like that. So yeah.

KIM: Yeah. Great. Lucy, thank you so much! This was a wonderful conversation. Love this book and love you.

AMY: Yeah, it was so great having you back!

LUCY: Oh, honestly, I’m just so grateful you let me come back and talk about, you know, this wonderful book, which I hope people read, but also McNally Editions. It’s a real pleasure to be here again. I love listening to this show, so please keep making wonderful episodes, ladies.

KIM: Oh, thank you. We will.

LUCY: And, um, hopefully see you again at some point!

AMY: Yeah! Absolutely.

KIM: Definitely. Bye, Lucy! That was super interesting, and I can’t believe the incredible people we’ve been able to talk with over the last couple of years, Amy. I’m pinching myself every day. It’s basically a dream come true!

AMY: And the good news is we have so many amazing guests coming up, right, in the weeks and months ahead. (And amazing lost ladies to talk about, too.) So we’ll sign off now, but don’t forget to subscribe to our newsletter, where we’ll let you know which books you can get a jump on for upcoming episodes.

KIM: Our theme song was written and recorded by Jennie Malone and our logo was designed by Harriet Grant. Lost Ladies of Lit is produced by Amy Helmes and Kim Askew.

85. Mary Taylor — Miss Miles with Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney

Note: Transcripts are generated using human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

AMY: Hi, everybody. Welcome to another episode of Lost Ladies of Lit, the podcast dedicated to dusting off books by forgotten women writers. I'm Amy Helmes...

KIM: and I'm Kim Askew and today's episode is Bronte-adjacent. I guess you could say.

AMY: Yes. In addition to her literary siblings, Emily, Anne and Branwell, Charlotte Bronte had a very close lifelong friend who was also a writer. Her name was Mary Taylor, and in some ways Taylor bears all the hallmarks of a classic Bronte heroine. She had a stubborn and rebellious nature. She was fiercely independent and she was a vocal feminist.

KIM: Yes. And unlike a classic Bronte heroine, she had no time for caustic jerks like Mr. Rochester. Far from being a love story, her 1890 novel Miss Miles: A Tale of Yorkshire Life 60 Years Ago makes the forceful argument that all women ought to have the right and the wherewithal to provide for themselves, financially speaking. She was basically fed up with the options available to women for getting by in the world.

AMY: So it's no surprise that such a girl-power themed book would have strong female friendships at the heart of its story. And I'm excited to welcome the two guests today who introduced us to Mary Taylor: Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney. We mentioned them last summer in our mini episode on literary sisters.

KIM: Right. And in that episode, we had put a wish out into the universe, just hoping these authors and friends might agree to come on the show. And we were so thrilled when they said yes. So without further ado, let's read the stacks and get started!

AMY: Our guests today are Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney. Emily's work has been published in The Washington Post, the Paris Review, Lapham's Quarterly, Time and elsewhere. She is a winner of the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize and her most recent book, which came out last year is Out of the Shadows: Six Visionary Victorian Women in Search of a Public Voice. She teaches at New York University London.

KIM: And Dr. Emma Claire Sweeney is a central academic at the Open University where she chairs and designs undergraduate and postgraduate creative writing courses. She's won the Society of Authors, Arts Council and Royal Literary Fund awards. And she's written for The Paris Review, Time and The Washington Post. She was named an Amazon Rising Star and a High- Rising Writer for her debut novel 2016's Owl Song at Dawn. It was inspired by her sister, who has cerebral palsy and autism, and it went on to win a Nudge Literary Book of the Year.

AMY: Together, Emily and Emma co-authored the 2017 nonfiction book A Secret Sisterhood: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf. In her forward to this book, Margaret Atwood described the work as "a great service to literary history." And I think I would just hyperventilate for the rest of my life if I got that kind of seal of approval. Uh, also A Secret Sisterhood was called "an exceptional act of literary espionage" by The Financial Times. So Emily and Emma, welcome to the show!

EMMA: It's a real pleasure and privilege. Thank you.

EMILY: I'm a big fan, as you already know, so it's really particularly great to be here.

AMY: Okay. So Charlotte Bronte's friendship with Mary Taylor is one of the four main friendships you guys focus on in your book, The Secret Sisterhood, but it does sound, in reading your book, that it required some sleuthing on your part to kind of piece together their bond. I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about the work involved with that.

EMILY: Yeah. So this is Emily. So although Mary Taylor is by no means a household name, if you've read a biography of Charlotte Bronte or the Bronte sisters, you will have probably heard of Mary Taylor. She was a close friend to Charlotte Bronte and also her sisters to some extent, but we were really interested in the literary influence that she had on Charlotte Bronte, both in terms of her creative output, but also really pushing Charlotte Bronte to establish herself as a professional writer. And we could talk more about the ways that Mary did that a little bit later in the interview. Um, but it did, as you say, require some sleuthing. I mean, sadly, very few letters between the two of them have survived. Mary destroyed a number of these letters in a fit of caution, she said, which we can only assume she was concerned about the letters' incendiary contents. And Mary Taylor was not usually a particularly cautious person, so it really makes one wonder what was there. So yeah, we had to find other ways of finding out about their friendship. Looking at the letters that did survive, looking at other letters to other individuals who had hung on to the letters, and also other things that Mary Taylor had written later.

AMY: Sounds juicy.

KIM: Yeah. So what were you able to find out about their early friendship? Do you have any favorite anecdotes about them from their school days together?

EMMA: Yeah. It's Emma here. Um, sadly they did not get off to the best start. It's actually a little bit heartbreaking reading about Charlotte Bronte's school years. She was ostracized for being shortsighted, for being diminutive in height, um, for being unable to really throw herself into the sort of playground games. And Mary Taylor didn't seem terribly impressed by Charlotte Bronte when she arrived at the school, and from what we can gather, didn't seem to do anything to defend Charlotte Bronte against the other children's laughter. And then at one point they did have an interaction and the story actually gets worse. Mary Taylor apparently told Charlotte Bronte, "you are very ugly." This was something that really haunted Charlotte Bronte for years to come, and, you know, she referred to it in later years. But at the same time, she did grow to really appreciate Mary Taylor's bluntness. She referred to "the sincere and truthful language" that her friend would use, because they did become friends. One of the anecdotes I love about them, actually, is that having got off to this terrible start, they ended up getting into political debates. Um, Charlotte Bronte was much more conservative as a school kid and she actually was really interested in politics from a sort of ridiculously young age. So they used to get into these quite fiery debates, because Mary Taylor was from a family of radical Nonconformists. So she had a much, much more progressive and liberal outlook. Um, so yeah, the idea that they were talking about these kinds of political subjects from a young age, I think said something about the two of them and perhaps shines a bit of a different light on Charlotte Bronte, because I think we often think of her as sort of quite timid. And I think in some way she was, but she also was very well-informed and not afraid to speak her mind when she felt that she knew her stuff.

AMY: And there was also another young woman in the mix, too, their other friend, Ellen Nussey. So how did Mary fit in along with Ellen?

EMILY: The three were very close, but Mary and Ellen were quite different individuals. Ellen was quite a gentle person, particularly as a school girl. Um, she was someone who was much more cautious than Mary Taylor. As we've already heard from Emma, Mary Taylor and Charlotte Bronte's relationship was much more robust. And Charlotte would go to Mary, you know, to thrash out thoughts on issues of the day, or maybe actually just to try and get advice of what she should do in her own life. So I think Charlotte needed both of them, but for quite different ends, I would say.

KIM: Yeah. And in some ways you really argue that Mary was instrumental in helping Charlotte Bronte become the woman we now know and love. Is that right?

EMMA: Yeah, I think we would definitely argue that. Um, when Charlotte Bronte was working as a teacher at the school they had formerly attended together, she was desperately unhappy. And Mary Taylor said, you know, "How can you give so much of yourself for so little money?" Because she knew that Charlotte Bronte wasn't managing to, you know, put much aside. So I think that encouragement to think beyond the conventional ways in which women of that class and time could earn a living and to take herself seriously as a writer, to think of that as something that maybe she could pursue. Um, and then If we know anything about Charlotte Bronte beyond the Haworth Parsonage in Yorkshire and the moors, we might know that, um, she spent some time in Brussels in Belgium, and that was a trip that was sort of instigated by Mary in many ways. Mary had planned to go there and study, and telling Charlotte Bronte about this, you know, inspired her to think maybe this could be an option for her. And she talks about Mary giving her "a wish for wings." So I think that sort of life beyond the sorts of family was a life that Mary Taylor kind of opened up in many ways. And then of course the radicalism that was inspired by Mary Taylor, you know, went on, we would argue, to shape a lot of the thoughts that we might associate with Charlotte Bronte in her later novels.

AMY: She also kind of had a tough-love attitude towards Charlotte, and that leads into her response to Charlotte's novel Jane Eyre. Can you talk a little bit about how she responded to that?

EMILY: Well, she responded in a mixed way, I would say. She did praise it as being, you know, a wonderful work of art. Um, she clearly could see that there was some literary merit with it, but really, you know, something that she really wanted to take Charlotte Bronte to task for was at least, in Mary's eyes, she felt that she had not included a strong enough social or political message. She said to her, you know, "Has the world gone so well with you that you have no protest to make against its absurdities?" Now, this may have come as something of a shock to Charlotte. And I think, you know, to us today, it doesn't actually necessarily feel like reasonable criticism because although Jane Eyre had been hugely popular when it came out, it had also been quite controversial. And the very thing that it has been criticized for in some quarters was, you know, challenging the status quo, presenting this woman who was not going to just fit in with the way things were done. And so I think all of that is there in Jane Eyre, but it was not perhaps right on the surface, because it's all wrapped up in the storytelling. Mary, I think, wants things to be on the surface. She wanted the political message, the social message to be right there, where everyone could see it.

AMY: That's exactly what she does with her book, Miss Miles. And so let's move on to this novel.

EMILY: Yes. So the subtitle of Miss Miles is A Tale of Yorkshire Life 60 Years Ago. The book came out in 1890, so we're talking, you know, the 1830s. It's a book that looks at the whole community, but it specifically looks at some key female figures within that community. The Miss Miles of the title, so Sarah Miles, who's a working class young woman who seeks to better herself. Although initially she doesn't even really know quite what she's pursuing with this idea of bettering herself, but by educating herself and trying to become independent. I won't go through all the different female characters, but two that I think are particularly interesting are Maria Bell, who is a clergyman's daughter who falls on hard times and then establishes herself as a school mistress, and really tries to make a go of things that way. And her friend, Dora Wells, who has actually got this quite dreadful family background in the sense that her mother has been left a widow and she remarries into a family, really, just with the aim of shoring up her own financial circumstances and for her daughter, as well. And to some extent this is successful, although not to the extent that she would have envisaged, but she also brings her daughter into an environment that's extremely unwelcoming, um, and really just a complete misery for Dora. And Dora really finds herself unable to extricate herself from the situation. And I think the friendship between Maria and Dora is particularly interesting because we do see aspects of Mary and Charlotte's own friendship kind of played out in the way that these two connect with each other. So I think it's interesting in terms of portraits of women of the time, but also anyone interested in the lives of Mary and Charlotte.

AMY: So the setup is kind of these four women from four completely different circumstances. And she's sort of using each one as an example for, you know, the difficulties that women face, including one of the ladies, Amelia is from a wealthy family, but we see a reversal of fortune in her case. But really, what Taylor's doing is exploring poverty and the workforce of the time and the fact that there were no safety nets. So a bad year at the mill meant, you know, possibly the poor house or starvation for people.

KIM: Yeah, I mean, she really gives us a frightening vision of what can happen to women when they aren't able to support themselves. And yeah, the same threat does hang over the men in the book too, but there's this feeling that at least they have some agency in the situation that the women lack.

AMY: Right. And Taylor kind of underscores this point when she writes about Maria, "For in truth, it amounted to this: that she had no more control over her own good will or ill luck than a little child." So what if anything from Mary Taylor's own life would account for her being so fiercely focused on this idea of wanting women to be able to support themselves?

EMMA: I think a lot of this, um, might stem from her relationship with her father. Her father had quite progressive attitudes towards marriage. He advised her not to marry for money, and not to tolerate anyone who did. And that seems to be advice that she took to heart and advice that was, you know, it was quite extraordinary at the time. But also her father went from being a really quite well-off industrialist to mounting debts and bankruptcy. And so, you know, Mary as a, as a girl, saw a real change in fortunes and, you know, went from a high level of comfort to having to take care of, I suppose, in terms of not having new clothing and looking out of place with the sort of more fashionable children at school. And then, when her father died and he had actually become bankrupt, there were tensions between her mother and her three brothers about the remaining property and assets, and the division of those. So I suppose that situation would have really highlighted to Mary the vulnerability of women when they're reliant on their menfolk to earn the money and make the financial decisions.

AMY: Right. And let's get back a little bit to this character of Dora that you brought up, Emily. This is Maria's best friend. Her mom has no other recourse to provide for them but to marry an abusive evil husband. Dora says at one point, "From what terrible destiny did she rescue me when this was the price? Once a beggar, always a beggar, she seems to have thought, and then accepted her position and took the means that are supposed to make all things right for womankind." Meaning, of course, that marriage was the only real option that she had.

KIM: So, yeah, we mentioned Taylor complaining that Bronte had no doctrine to preach. Well, Taylor preaches in Miss Miles. Boy, does she! And oftentimes it's via Dora. She actually says to Mariah, "Darkness is ignorance, I tell you. It is what is recommended to us women. If people knew that the women in the church yards were alive, those in the coffins I mean, and were waiting for us to dig them up, do you think anyone would do it? No, they would not. They would say ladies did not want to get up. That they had all they wanted and the men did not like them to get out of their graves."

AMY: Yeah, she really doesn't hold back. And then she has hatched this idea, like her one long shot, Hail Mary pass that is going to get her away from this horrible house she's living in. She's going to try to be a lecturer. Kim and I were cracking up because she has no experience. She doesn't even basically have a speech prepared. She's just going to wing it when she gets up there. But she gets Mariah to go out to all her neighbors and sort of gather them together, sell them on the idea of paying for this lecture. And then when Dora does give her speech, it's a moment, right? She brings the house down.

EMILY: And do you really do get the sense that the people who have turned up for this speech, you know, they've basically come for the novelty of seeing this crazy woman getting up and, and giving a talk, which I think we do have to remember how unusual, how novel it would really be to see a woman standing up in public and speaking about anything, really, at that stage. And she talks about social issues, really in the speech. You know, she talks about the plights of working people. We get the sense that Dora has been pushed to breaking point, but we also get, of course, the sense of Mary Taylor, the author, using Dora as her mouthpiece to say, you know, what she really thinks. So it's interesting, I think again, from those two points of view, and, um, as you say it's a speech that's extremely well-received in the book, and it marks a complete shift in the way that Dora sees herself as a character, and it allows her to finally see a way forward in what has become, you know, a very long, drawn- out, dreadful situation for her.

AMY: Yeah. And so like you said, the people in the town are not just skeptical, but a little scandalized by it too. And in fact, Maria has this would-be suitor who is trying to win her heart. And he sends her a letter, basically, lecturing her about her friendship with Dora and saying, "You should not be associating with this woman. It doesn't make you look good." A super annoying letter. And I love the fact that she writes him back with this mega "talk to the hand" moment.

KIM: Yeah. I mean, Amy and I texted each other when we were reading that part, like, "Oh my God, this is great." She's like, "no." Um, and then also another thing that happens is Sarah punches her love interest in the face. So there's this visceral female strength happening in both of these different ways, and throughout the book. Do we know if any of this squares with Mary's relationships with men in real life?

EMMA: Well, it's hard to imagine that Mary was the kind of woman who would put up with any kind of mansplaining. And the kind of upbringing she had from a father who encouraged her not to marry for money probably set her up quite well, that feeling that she had a right to some kind of equality and independence. I think she liked to be able to do the things that men might be able to take for granted. One of the lines from one of Mary Taylor's letters that I particularly love, and I think it gives a real sense of her character, she was talking about studying algebra and she said "it is odd in a woman to learn it, and I like to establish my rights to be doing odd things." I think that sorts of sums Mary up, really.

KIM: What a great quote. Oh, I love that.

AMY: She sounds like just a spitfire.

KIM: Yeah. I love her.

AMY: Um, in the book, I think Mary Taylor throws more than a little shade around at upper class women and even some middle-class women. They don't always come across particularly well in the book. In fact, um, the young woman, Sarah, who's decidedly from a lower class, she has these great fantasies about being like a fancy lady someday. "I want to be a fancy lady" and then she would always stop and be like, "What do they actually do?" And then people would kind of explain "Well, they do this or this." And she's like, "No, but I mean, what do they do?" I love those moments.

KIM: Yeah. The more she found out about it, the more she was kinda like, "Hmm. I don't know about that."

EMILY: Yeah. There was a sense of how even people who are in relatively comfortable social positions can be trapped just by the nature of being a woman and having so little agency, so little control over their own fortunes, you know, other than marrying a rich man who may or may not treat you well. Whatever you say about Miss Miles, there is a strong social message to it. You can see what the argument is, and I think that could only really have been honed through years of experience and years of thinking about the subjects that she wants to include.

AMY: Yeah, I, I kept thinking like, why did it take her so long to write this? But then when you think about her life, it does make sense because she was working, basically. It's like any career woman having to try to write on the side, and we'll get into this in a moment, but let's back it up a little. So in the autumn of 1844, Charlotte received a letter from Mary that shocked her to the core. Mary announced that she was moving to New Zealand. And Kim, I couldn't help but think of the moment, long ago, when you told me that you were moving from LA to San Francisco, and I'm pretty sure we both burst into tears.

KIM: Yeah, I'm sure we did.

AMY: Luckily Kim came back, but I know that feeling of like, "Oh my gosh, my best friend is leaving. Like halfway around the world." Luckily San Francisco was a lot closer. Um, can you talk a little bit though, why Mary made this move and why it was such a pivotal move for her?

EMMA: Well, she had seen her brother make this Intrepid move, and I think she had realized that in New Zealand, British social mores had not embedded themselves. The kind of conventions were more malleable. And so I think she thought of it as a place where she could be pioneering. She could be part of a process that was defining what that culture might be, for better or worse. On the plus side, as a British woman traveling, she was afforded a huge amount more independence than she could have hoped for back in Yorkshire. So she ended up, you know, building, I assume, not with our own hands, but commissioning a five-bedroom rental property to be built. So she was able to get this, this rental income in. She helped her brother with his import-export business and she honed these entrepreneurial skills, which she then later used when a cousin of hers joined her in New Zealand and the pair of them ran a shop together, All of these things things would have been quite difficult for her to have engineered as a middle class woman in Britain at that time. And it was a pivotal moment for Charlotte Bronte, too, I think. I mean, you know, you two were talking about how devastated you were when you were going to be moving further apart. And I mean, Charlotte Bronte referred to Mary Taylor's news as "feeling like a great planet falling from the sky." And so, in a way, I think it was pivotal for Charlotte, just as it was pivotal for Mary. Partly through hearing about this alternative way of life for a woman, and it feels to me that in some subtle way shaped Charlotte's own thoughts about female independence.

KIM: That makes sense. That makes complete sense. So when she got to New Zealand, that is when she supposedly started writing Miss Miles, maybe, um, even though she didn't finish it for 40 years. Is that right?

EMILY: Well, there is a letter where she talks about how she's working on her novel. She doesn't specifically call it Miss Miles. Perhaps it wasn't called Miss Miles at that stage. But I think it was this book or something similar to it. But even then at this stage, she says, you know, she doesn't have that much chance to work on it. She was so busy with other things. You do get the sense that this is something that is being put on the back burner while she concentrates on doing other things.